severak

2.7.2020 16:54:40

severak

2.7.2020 16:54:40

There is so much “fake history” going around about the Medieval Era that I decided to write this article and create this;

There are a lot of myths and misconceptions about “The” Middle ages.

This era lasted roughly 1000 years and life was very different at certain times and in different places, so it is a bit silly and difficult to make blanket statements about this subject.

Nevertheless when talking about Medieval Europe or seeing movies set in that era so many things are brought up that are totally incorrect.

And yes some of these myths are still being taught in schools and are thus quite common.

Many of these misconceptions come from Victorian writers and historians who reflected their Victorian society into how they thought Medieval life was.

So I made this fun Medieval Myths Bingo card.

Print it out and get it ready when watching yet another Hollywood blockbuster set in the Medieval era, or bring it along to museums and school lessons.

What I have written here is based on the opinions of modern day historians and experts who generally get their information from actual Medieval records, archaeological finds, evidence and other sources.

Don’t take my word for all of this being the absolute truth, use the links I share and also do your own research before making your mind up.

Remember though; the Middle ages lasted 1000 years and some of these topics relate to the early Medieval period, some to the late.

And Europe was and is quite large so some bits are about England, some about France, etc.

When I speak of Europe in this article I mean the region we call Europe today.

Also; this is a work in progress.

I welcome improvements and corrections, also in the text below and if need be in the Bingo card.

Please leave comments.

Quick links;

- Everyone has bad teeth

- Nobody gets old

- Always war

- Only the clergy could read

- Women have no rights or jobs

- Pigs & chickens in the street

- Empty chamber pot from window

- Common people never wash

- Everyone was short

- Earth is flat

- Vikings with horned helmets

- Nobody drank water

- Witch burnings everywhere

- Knight’s armour too heavy to move in

- Bland and tasteless food

- People never travelled

- Not racially diverse

- People were ignorant

- No Medical knowledge

- Death penalty common

- No table manners

- Torches all over the place

- Two finger salute

Everyone has bad teeth

Although dental care was not as advanced as it is today Medieval people also had less need for it as their diets generally didn’t contain (much) refined starches, sugars and acids.

The modern diet is a lot better for the bacteria that love damaging teeth and enamel. We consume soda, candy, additives but also tobacco and coffee, all bad for your teeth.

Medieval people had no or very little access to ingredients and foods that were really damaging to their teeth.

They also cleaned and brushed their teeth, there are many Medieval recipes for tooth care and they used rags to rub their teeth with.

There were even tooth brushes but also used chewed twigs as brushes, the Glycyrrhiza glabra plant was and is especially well suited for this job, it is better known as the Liquorice plant.

These “chew sticks” have been used for thousands of years all over the world.

Tooth care wasn’t invented by one person or group but probably by people all over the world when they started having issues with their teeth.

There’s evidence that suggests prehistoric cavemen even used twigs to clean their teeth (source).

There were also tooth whitening recipes, mostly herbal and quite harmless.

Archaeological finds have shown that although the teeth on Medieval skeletons generally show more wear and plaque and tartar but they also showed a lot fewer cavities.

Of course their teeth would not look like the unnatural way that is fashion today in some countries; lined up straight, so white it hurts your eyes, etc.

Toothache was a big problem and although often the only cure was a prayer there is also evidence for quite sophisticated dental intervention.

But they would not be black, rotting, or falling out all the time either, like we often see in movies and on TV.

Of course if plaque went untreated and turned into tartar the teeth would look yellow and smell bad, however this too kept bacteria from actually damaging the teeth underneath.

And yes, if they did have a problem with their teeth the damage would be more extreme and often also not camouflaged with fake teeth.

So if you did get an abscess, cavity or other problem you’d lose your tooth/teeth and spend the rest of your life walking around without it, something that doesn’t happen very often today.

It wasn’t till the 15th century that they started drilling teeth and filling holes with gold.

Interesting quote;

“When you get up in the morning, stretch your limbs, so that the natural heat is stimulated. Then comb your hair because this removes dirt and comforts the brain. Wash your face with cold water to give your skin a good colour and to stimulate the natural heat.Clear your nose and your chest by coughing, and clean your teeth and gums with the bark of some scented tree.”

Taddeo Alderotti, ‘On the Preservation of Health’, 13th century,

So I’m not saying Medieval people didn’t have bad teeth and dental problems, they did, but their teeth were not as bad as most people seem to think.

Sources;

Medieval Teeth

Dr. Gary J. WayneOral & Maxillofacial Surgery

Dental treatment in Medieval England

Nobody gets old

Life expectancy figures in Medieval times weren’t very high but that is because high child mortality rates are often included in the calculations.

A better insight in life expectancy can be obtained by looking at people who survived childhood and how old they were when they died.

Looking at church registers and the skeletons found at archaeological digs we can see that it was not that uncommon for people to live into their 60s and even 70s.

Of course many people still died much younger, women for instance risked their lives every time they got pregnant.

This puts life expectancy for those who survived childhood quite close to what it is today and even a little higher than it was for much of our history after the Medieval era.

Although it is of course impossible to say anything about this subject for the whole of the Medieval era and world as situations differed immensely between certain regions and eras.

Nevertheless we can safely say that the idea of people never or rarely living past their 30s is a myth.

Sources;

The Life Cycle In Western Europe by Deborah Youngs

BBC ‘Do we really live longer than our ancestors?’

‘Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course’ by Roberta Gilchrist

Always war

This era is often depicted as violent and one of wars continuously happening. But we get this skewered view of the era because wars is what is written most about, daily life just wasn’t that interesting to historians a few decades ago.

It was not at all strange for a Medieval person to live their entire life without experiencing war.

Only the clergy could read

Although education was not available for everyone it is also not true that only the clergy could read. Although it is impossible to find out how many people could read/write during the Middle Ages (and which part of this era and where in the world!) there are plenty of sources that show that plenty of peasants, merchants and others could indeed read and write.

Women have no rights or jobs

For much of the Medieval era in much of Western Europe women had more rights than most people think and it was the Renaissance when they started losing them.

On top of that many also owned shops and had jobs.

Sources;

Going Medieval

Pigs & chickens in the street

Although animals sometimes did walk around towns and villages, it wouldn’t be the chaos we often see in movies.

Chickens and pigs were valuable and owners of course didn’t want to risk losing them or them getting wounded, lost, etc.

On top of that Medieval people, like us didn’t want their stuff covered in excrement.

Pigs were generally kept in pens or walked free in the woods when they belonged to a lord.

Of course chickens, cats and other animals are difficult to contain and surely they walked around freely by farms, in a city or town people would try to avoid that.

Not only were there sometimes rules and laws about this sort of thing, it is also common sense.

You wouldn’t want them to get lost, you would want to know where you had to look for the eggs and on top of that you can imagine what it would be like if chickens walked in and out of houses.

In Medieval times houses often didn’t have glass in their windows and the door was open a lot, in summer time probably permanently.

Which would mean that any animal could walk in.

Would you want that?

Empty chamber pot from window

This did happen but not really in Medieval times.

Of course I am not saying it never happened, but many people have this idea of Medieval cities having this problem and that it was so common that people would shout “gardyloo” (Gardez à l’eau, look at the water) as a sort of warning.

Again this is one of those things that really was a thing but at the very end of the Medieval era and after that.

Till the Renaissance most cities and towns were not yet that overpopulated and often had an agricultural character, with other words most houses had a garden or yard, an outhouse in the back, etc.

There was no reason to empty a chamber pot out of your window.

Why would you risk a fine or being stabbed in the face by whoever happened to be walking underneath your window if you could just as easily dump it on your compost heap at the end of your garden or save it and then sell it, as it had some value.

At this time most houses didn’t even have an second floor which would also make this a bit difficult.

When the cities and towns started growing and getting overcrowded things went wrong.

This is when people started building taller houses but also the space in these areas became so valuable that gardens and yards started getting smaller and disappearing.

Also in towns and cities you no longer really needed a garden because there were shops and markets where you could buy the herbs and vegetables you grew there, trade became a bigger part of daily life than it had been before.

But this also meant more people lived in small areas while they no longer had space to put an outhouse, their own well, or where to dump their waste.

And with taller houses it also meant that in many cases the people at the ground floor perhaps still had a garden or yard but the people living on the top floors couldn’t use it.

You can imagine that when you suddenly have to carry your waste to a special dumping area or wait for it to be collected, the temptation to throw it somewhere where you were not supposed to started to become very tempting.

As always in history; overpopulation causes trouble.

Medieval records show people complaining and getting very angry with neighbours who made a mess or caused discomfort.

Fines in 14th century London could be levied against anyone living near the place where filth was found, so if you saw your neighbour dumping waste in the street you know you’d be at risk of a fine as well.

Other examples show that someone caught merely urinating in the street was almost beaten up by locals for doing something so filthy and a man who threw just a fish skin on the street caused the owner of the house to be fined for it who then got so angry he beat up the litterer.

If anything, old records seem to suggest that Medieval Europeans tried really hard to keep cities and towns clean and most examples of people getting really rather filthy come from later.

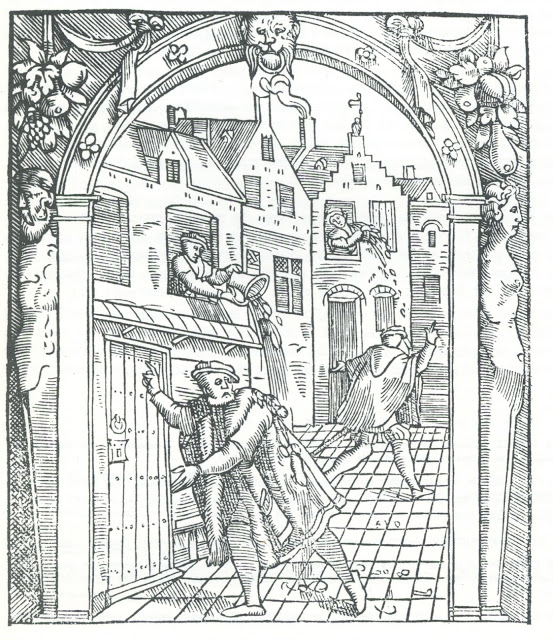

This wonderful illustration is from 1555 for instance;

At about the same era, the 16th century (so technically just after what we generally consider to be the Medieval Era) we see several new laws popping up regarding the handling of waste in Belgium.

Including a very specific law stating that windows overlooking a neighbour’s yard or garden needed bars so a ‘piss pot’ could not be emptied out of this window.

It seems that although this had happened before, it did become a serious problem at the end and after the Medieval era.

And even then foreign visitors praised the low countries for it cleanliness and neatness.

So even when it was something that needed specific laws, it still was not something that, at least in Antwerp, seems to have turned the streets into one massive cesspit.

Of course things often went wrong and there were plenty of accidents and incidents where indeed people ended up complaining about a filthy stench or waste everywhere.

But the idea that this was not just common but actual daily life for all of Medieval Europe all the time is the myth.

In this era people connected smell with health, bad air was assumed to be unhealthy.

So besides just not liking bad smells our ancestors had an extra reason to want to try and fight unhygienic situations.

They were not this different from us; they did not enjoy living in filthy, smelly and dirty looking towns and fought hard to try and avoid/fix this when it happened.

This is one of the few images that shows someone emptying what could be a chamberpot from a window which is often used as an illustration of this bad habit.

But it was published at the very end of the Medieval era and the emptying is clearly not done out of laziness or habit but as a subtle way to show ones opinion of the musicians making a racket late at night.

From Sebastian Brant’s ‘Das Narrenschiff’ (Ship of Fools), Basel ca. 1497

In short; there have always been dirty naughty lazy people who dumped their waste out of windows but in much of Medieval Europe this seems to have been a rare crime that both law enforcers and neighbours would react harshly to, just like today really.

The waste was mostly dumped in ones own yard, given to a collector or taken to a communal dump or special river, stream or gutter meant just for this purpose that would have flowing water in it and thus not cause much of a stink, unless it got clogged and well, that would be horrible.

When cities became overpopulated, this relatively well functioning system collapsed.

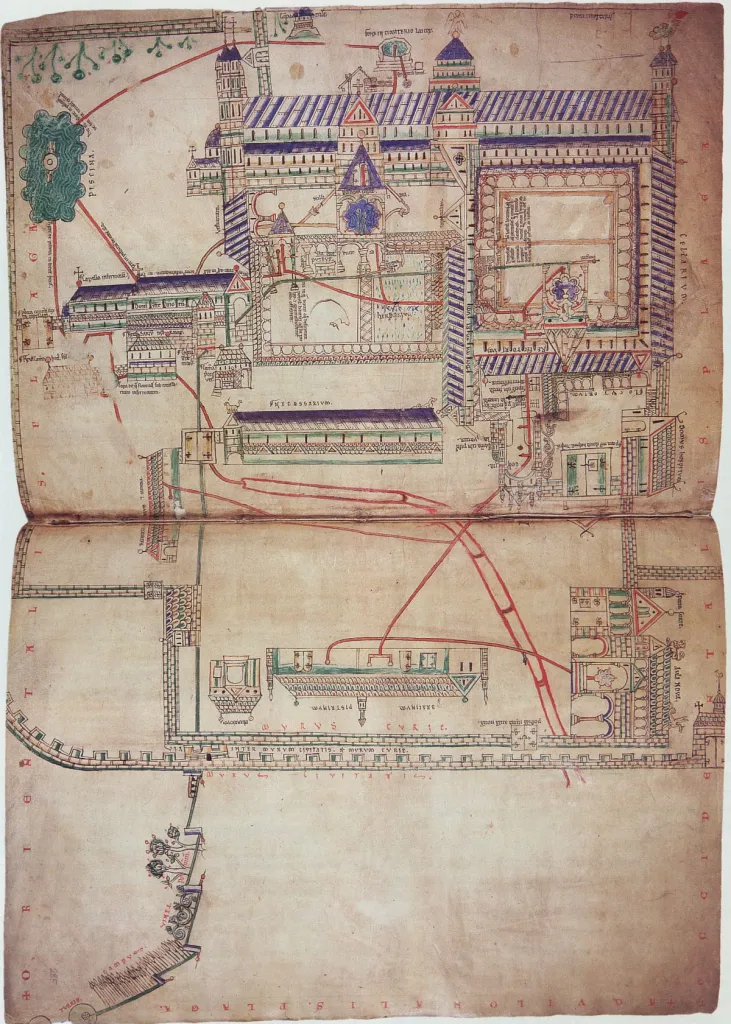

Map of water supplies in and out of the Christchurch abbey in Canterbury from the 1160s.

With springs, holding tanks, water being piped through to basins, kitchens and toilets

Sources;

TodayIfoundout

Wildevrouw

Tim O’Neill

Medievalist

Waste Management and Attitudes Towards Cleanliness in Medieval Central Europe

City Sanitation Regulations in the Coventry Mayor’s Proclamation of 1421

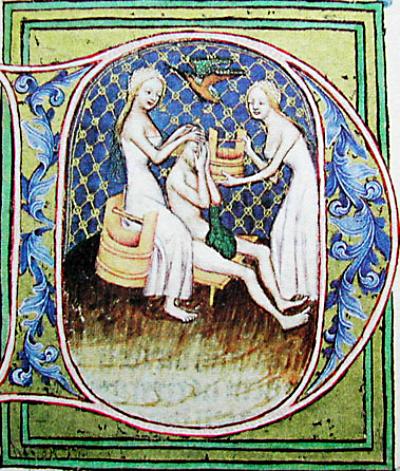

Common people never wash

Medieval people cared a lot about hygiene and washed, often daily, yes even the poor.

Because sources tell us people rarely took a bath we assume they didn’t wash, but having a bath isn’t the same as having a wash.

Having a bath generally involved filling a big tub with hot water, which often meant boiling water over an open fire, carrying it in buckets to this tub, lining it with fabric (splinters!), adding herbs, soap, etc, this it took a lot of time and effort and thus was something that wasn’t as easy as it is today.

However getting a smaller amount of hot water was a lot easier, simply by placing rocks in the (always burning) fireplace, waiting for them to be hot and then placing them in a bucket or bowl would get you hot water easily and quickly.

We know from Roman Historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus that Germanic tribes started their day with bathing, often with hot water (source)

But although a big tub lined with fabric filled with lots of hot water wasn’t something everyone could do every day, washing yourself with water from a bucket or jumping in a pond or river was available to everyone.

People cared about hygiene, even peasants and farmers.

People were advised to change their underwear daily and pretty much every household account book is full of payments to washerwomen.

Besides the washing from a basin there was of course almost always access to clean water because cities, towns and villages were in most cases built near a stream, river or lake, but there were also a lot of bath houses, they were extremely popular and much used.

And of course there had been Jews in Europe since Roman times who bathed quite regularly as part of their religion.

Although of course indoor plumbing was rather rare in Medieval Europe, it also wasn’t unheard of.

Some palaces, monasteries, abbeys and even rich houses had running water and ways for used water to leave the building.

In Britain the The Worshipful Company of Plumbers was founded in the 14th century and much of their work involved installing, repairing and maintaining conduit pipes.

Both Exeter and London had networks of tunnels and pipes bringing fresh water into the city, those who could afford it in some cases could request extra pipes to be connected to their home or place of work, such as brewers, cooks, fishmongers, etc.

When Henry VI processed through Cheapside in 1432 on his return from France, the Conduit was used to provide free wine to the masses, people could fill their jugs from public fountains across London.

With all its failings at least that is one bit of Medieval plumbing modern society wouldn’t be able to 😉

The Medieval soap industry was huge in Europe, Naples had a soap maker’s guild since the 6th century and soap making was done by men and women, often well trained, but soap had been used in Europe for possibly thousands of years.

The Greeks had known how to make soap for millennia but the Gauls, Celts and Germanic Tribes are all known to have also manufactured and/or used soap long before the Roman invasion.

The Romans didn’t really use soap till then, they used oils to clean their bodies with.

But they appear to have been very impressed with the soap they found when they conquered Western Europe, especially German soap was seen as the best according to Aelius Galenus (AKA Claudius Galenus, Galen or Galen of Pergamon), a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire (129 AD – c. 200/c. 216) although some historians argue that the sources of these claims were perhaps not by Galenus.

Romans started transporting the soap they found in Europe all over the empire, considering Germanic soap the best there was.

Either way it was considered to be of uniquely high-quality by scholars in Egypt, Rome, and Palestine.

Several sources mention the use of soap in Europe in early Medieval Europe, this was mostly locally made soap but this changed when the ‘Moors’ invaded Spain and trade and contact between Arab and European people became more intense.

Soap made by Arabs was of higher quality because they used ingredients like olive oil and nice smelling herbs that weren’t available in Europe, they also may have invented the soap in bar form which is rather handy and it soon became more popular than local soap.

At first soap like this was more expensive because of transport and ingredients but quite quickly Europeans started importing the oil and made their own soap.

But Medieval people knew several relatively easy soap recipes with ingredients and techniques that were available to even common people.

The church did have a few objections towards bathing, but not because they thought being dirty was better.

Gregory the Great (c. 540 – 604) recommended Sunday baths but also warned that they shouldn’t become a ‘time-wasting luxury’.

Vanity, sloth, laziness, the idea of people just hanging around in a bath for hours for pleasure was just not something the church approved of.

So the church didn’t object to bathing but to bathing too much.

Of course it was also considered vain and quite a few religious people, priests, nuns, etc, would consider not bathing as something rather pious.

But that also meant that people may have claimed, even bragged about not washing when they actually wear, just to look ‘cool’.

A bit like modern day people bragging about their no-make-up face or sharing a ‘selfie’ of how they look just waking up while they secretly spend a lot of time and products on that look.

Lucas Rem, 16th century tradesman in the German town of Augsburg bathed 127 times within three weeks, according to his diary.

I bet that’s more baths than you had this month.

In some towns you could be fined if you didn’t visit a public bath once a week.

Bath houses were very cheap but for those who couldn’t afford them there were of course still lakes and rivers.

City records tell us that a lot of people drowned while bathing.

In early Medieval Ireland offering your guest a bath was basic hospitality, not offering a visitor the opportunity to bathe, or at least wash hands and feet, was considered an insult and yes that was not just among the nobility and rich.

But of course, when men and women get naked and sit in hot water while often having a drink as well, things can get a little naughty.

That is another reason the church started objecting to these places of debauchery, they didn’t ban them but they sometimes started their own bath houses, to keep people from bathing and sinning at the same time.

On top of that the plagues that became a returning horror in the late Medieval era also damaged the popularity of these places.

With highly contagious diseases going around killing millions, people started to avoid bath houses, after all when you thought you could get sick from a touch or even breathing the same air, you really don’t want to get in a tub with some strangers or visit other busy public places.

The famous Dutch philosopher Erasmus wrote in 1526;

” Twenty-five years ago, nothing was more fashionable in Brabant than the public baths. Today there are none… the new plague has taught us to avoid them. “

On top of that a tax on soap was introduced in England in 1712, this of course increased the price of soap immensely, making it a luxury.

That is why when the Medieval era ended and the Renaissance began, the state of hygiene started going downhill in many cities.

Many of the filthy hygiene stories date from that era, once more the so called Renaissance that put an end to those oh so horrible Middle Ages caused some of the bad things the Medieval era is accused of.

Also, it is quite interesting that people seem to think that at this time cultures outside Europe were somehow cleaner and more hygienic.

This is generally based on (rarely unbiased) observations from travellers but also because people with strict, often religious hygiene practises like the Wuḍū in Islam and the netilat yadayim in Judaism, which generally involves the washing of hands.

These still play a big role in these (and other religions) but not so much in “The West” where religion has stopped playing an important part in the lives of many people.

But in Christianity there are also many ritual hygiene rules & habits.

The Black Death pandemic originated in Asia and was also killing countless people in the Middle East and Africa, it was not just a thing in Europe, hence it being a pandemic, not an epidemic.

But even in Europe several cities managed to avoid the plague and some areas were less affected than others even though there is nothing that suggests that hygiene circumstances were remotely different in those places.

The Black Death was came originally from the fleas on rodents but when it jumped to humans they became the main spreader.

Fleas & rats don’t travel as fast as the Plague did, it was people who were to blame for escorting Death along the Silk Route, on horseback, on sailing ships, from town to town.

The places that were spared just got lucky, were not along a trade route, were remote, didn’t get many visitors, etc.

Isolation is what saved people, not soap.

Of course all communities, especially large ones, have areas and certain inhabitants that are not as clean as the rest.

Streets where butchers or tanners worked, the neighbourhood where the poor lived, etc, could have had extra unhygienic situations when the strict rules and laws were ignored and when they had not (yet) been forced to do their work outside the city walls.

Judging an 1000 years era in a region so large as Europe based on extreme situations in some streets in some cities is of course ridiculous, after all, there are still modern advanced cities to this very day that have certain areas that can be called disgusting.

However till the very end of the Medieval era and the beginning of the Renaissance most Medieval cities just were not that large and still had a strong agricultural character.

With other words most houses still had a plot of land with room for an outhouse, cesspit and often even a well, although in many cases this was just a hole in the ground.

Of course this also means that even though Medieval people were clean and washed regularly, their way of life still attracted vermin, after all in a way most of them still lived on farms even if they weren’t farmers.

A house with a garden, a cesspit, some animals, would always be an attractive place to visit for all sorts of animals and bugs.

Caring about hygiene was also not something Europeans were taught later by interaction with other cultures, they’d been obsessed by it since before Roman times.

Of course, as always, interaction with other cultures taught them new things and introduced them to other , sometimes better ways.

On the other hand foreigners visiting a new part of the world would almost always have trouble understanding the local habits and would often consider certain traditions barbaric or dirty even when perhaps they were just different.

For instance Muslims and Jews were and are used to bathing/washing several times a day, for prayer, to them people who do things differently or for whom washing hands isn’t a ceremony but something they do privately and quickly, may seem dirtier.

After all humans had a habit of judging other cultures and their habits based on their own without bothering to try and truly understand the way others do things.

Even today in some parts of the world some people shower in the morning and before going to bed, which seems totally over the top to many others.

And when some considered the Vikings to be very clean because they spend a lot of time on their appearance, others considered them rather filthy for an entire household sharing the same bowl while washing.

Always be critical of the sources for such stories.

A Priest called the Vikings too clean, a Muslim called them dirty, these were both outsiders who could perhaps not be considered totally unbiased.

Vikings themselves have stories about bathing, left behind lots of hygiene products, etc.

If you truly want to understand a cultures hygiene habits, look at their own sources if you can, not (just) what outsiders said about them.

Interesting quote;

“When you get up in the morning, stretch your limbs, so that the natural heat is stimulated. Then comb your hair because this removes dirt and comforts the brain. Wash your face with cold water to give your skin a good colour and to stimulate the natural heat.Clear your nose and your chest by coughing, and clean your teeth and gums with the bark of some scented tree.”

Taddeo Alderotti, ‘On the Preservation of Health’, 13th century.

One of the oldest fresh and wastewater systems (and even a possible indoor toilet) ever found appears to have been built into several houses in Skara Brae just of the Scottish coast, a Neolithic settlement from around 3000 BCE.

Some of the houses even had “cell-like enclaves” which may have functioned as indoor toilets.

On a side note, although the Chinese already used toilet paper they didn’t use water to clean themselves after a toilet visit which Europeans might have done, after cleaning with a scraper, moss or straw, unfortunately this was not a subject people wanted to record long detailed historical records about back then so we have to mostly guess.

With other words, Europeans, just like people everywhere else, seems to have cared about washing themselves for pretty much all of history.

It wasn’t till the end of the Medieval era that it started to go wrong dramatically, cities became overpopulated and overcrowded, houses lost their little plots of land and with that lost their personal cesspits, outhouses, wells, etc.

Where- and whenever large groups of people live in a small area hygiene always suffers.

We know that many Medieval people were infested with roundworm and tapeworm, fleas and lice.

No matter how much they washed, combed and cleaned, living in densely occupied communities with a lot of trade traffic and surrounded by animals, in houses that no matter how much they tried could not be kept vermin and bug free, meant that the situation got worse and worse and eventually perfect for the fleas and lice that carried the Bubonic Plague and the animals (and people) they travelled on.

Nevertheless most of the stories we know about disgusting, filthy cities date from after the Medieval era when cities became truly overpopulated.

So what did Medieval people smell like?

Smoke.

Regardless of them washing every day with soap, using perfume or never washing at all, they and much of their world generally smelled of smoke.

Every house and most rooms had an open fire blazing away almost all the time, this is how people kept warm but also made sure they always had some warm water.

They sat around it, women slaved over it.

I have done this, I’ve lived the live of a Medieval woman in an reconstructed 14th century house in an Archeological park and from my own experience I can tell you that my woollen clothes, linnen undergarments, headcover, stockings and hair were all impregnated with the smell of smoke and it overpowered pretty much any other smell, even after days of cooking on hot fires during a heatwave, wearing 2 layers of clothing and no washing.

A little side myth; Most Medieval people married in summer because that is when they took their yearly bath and carried a wedding bouquet to mask the smell of the bride when the bath had not been very recent.

As stated above we know people washed, bathed, used soap.

Especially on occasions that supposedly would end with two people sharing a bed together, people would have a bit of a wash.

Part of the myth is that this is why summer weddings were so popular; lots of flowers.

But in Medieval England for instance, in rural communities, winter weddings were much more popular which makes sense because there was less work to do on the land and there would be fresh meat for the party.

Flowers were symbolic, nothing more, nothing less.

Besides have you actually tried this?

Stop washing for a few days or weeks and then go chat with your friends while carrying a bouquet of flowers.

Do you really think a few flowers will mask that smell?

Sources;

Going Medieval

TodayIfoundout

Ancient History

Medieval Soap making

The Book of the Civilised Man: An English Translation of the Urbanus magnus of Daniel of Beccles

Trotula de Ruggiero’s 11th century treatice, De Ornatu Mulierum

Life in Medieval Europe: Fact and Fiction

Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England

Aeon

Yes, People in the Dark Ages Bathed, by Kim Rendfeld

Cleaning and sanitation: a global history, by Giulio Guizzi

Toilet guru

Medievalist

Roger Pearse

Aeon

ThoughtCo. on weddings

Planet Wedding: A Nuptialpedia

Pre-Medieval hygiene history;

Naturalis Historia, by Pliny the Elder

A history of Greek fire and gunpowder

On the Causes, Symptoms and Cure of Acute and Chronic Diseases, by Aretaeus of Cappadocia

De Methodo Medendi, by Galen.

De Bello Gallico, by Julius Ceasar

Exeter plumbers

A Tale of Three Thirsty Cities by Jaime-Chaim Shulman

Water supply of the late Medieval and earl modern town in the Polish lands by Urszula Sowina.

Health, Grooming, and Medicine in the Viking Age

Everyone was short

Archaeological finds show us that the skeletons of our Medieval ancestors were not much shorter than our grandparents were during the 1930s.

Which roughly is about 10cm shorter than we are today.

Small doors in castles, small beds and children’s suits of armours made us think people were tiny back then but of course we also think that if we’re taller than our grandparents the further we go back in time the shorter people were.

But the small doors had other reasons, people often slept half sitting in beds and how tall we are depends on how well we live, not the era we live in.

Dirty, muddy streets

Although of course many villages and towns had dirt roads that would get muddy when it rained, paved streets were also common and there also often were gutters to help rain drain away.

On top of that many towns had strict rules regarding what people were allowed to do and not to do with the bit in front of their homes.

Not keeping it clean, throwing rubbish outside your front door, etc, could get you a nasty fine.

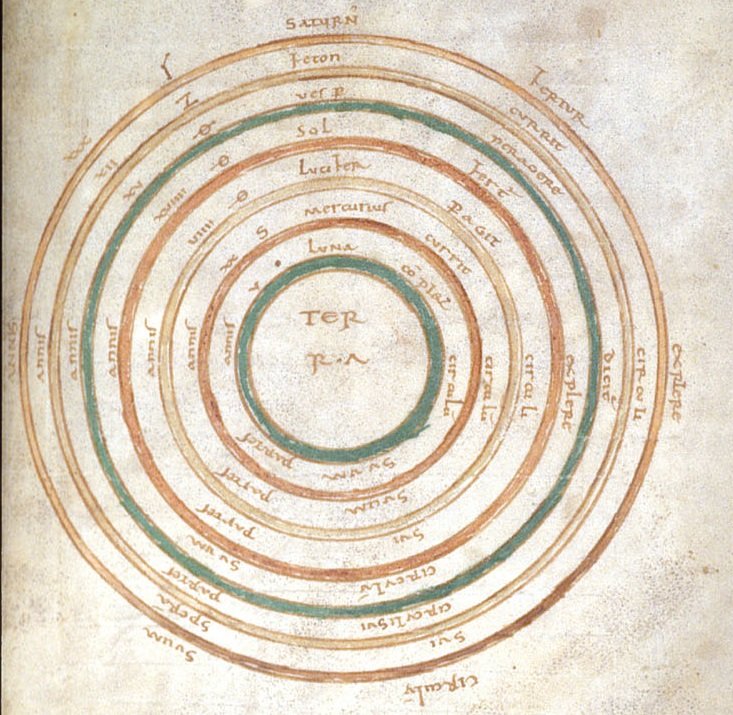

Earth is flat

There is no evidence that suggests that the belief that the earth was flat was very common in medieval times.

Of course there were people who did believe this but one of the few sources we have comes from Copernicus his book ‘De revolutionibus’ of 1543 where he describes Lactantius as someone who “Speaks quite childishly about the Earth’s shape, when he mocks those who declared that the Earth has the form of a globe”.

So we do have one source that shows someone who doubted the world being a globe being ridiculed.

Victorian anti-religious propaganda and the romantic movement of the era are guilty of misinterpreting a few sources and incorrectly assuming that the Victorian tension between the church and science were even worse in Medieval times.

The church supported science and the arts back then and it wasn’t till scientists started to discover things that clashed with the story of the bible that the relationship became tense.

In Medieval times the church assumed science would only help them understand God and the world he supposedly created better.

In short; there is no evidence that suggests that people generally thought the earth was flat.

Unlike today…

Vikings with horned helmets

There is no evidence whatsoever that suggests that any Viking ever had horns on his helmet.

The end.

Nobody drank water

People think that people drank wine and beer because the water was too dirty.

This is nonsense.

People did drink a lot of (light) beer and wine but water was also very popular.

People may not have quite understood how bacteria worked but they put a lot of work and effort in keeping their wells and other water sources clean and unpolluted.

And, of course depending on where you lived, there often were plenty of fresh water sources.

In the Low Countries people could easily dig a hole in their yard and get fresh water but also when there was a river nearby people probably knew that digging a hole next to it would give them relatively clean and sand filtered water.

Wells are being found during archaeological excavations all over Europe.

Settlements, towns, villages, cities, etc. all seem to have had people digging wells wherever they could.

As these places still had a highly agricultural character and most houses would have had a yard or bit of land behind it, people often had their own well, or more than one.

I myself once examined an 16th century Dutch house in a medieval city that showed evidence of having at least 7 wells dug by its inhabitants over the years.

Not just outside either, they seemed to have lifted a few tiles in their home, dug a hole till they found water and used it till the no longer needed or wanted to use it.

But besides wells there are also examples of cities bringing clean water from outside the city walls into the city

In short; there is plenty of evidence that shows people drank water, there is none that they didn’t or even thought that drinking water was somehow always unhealthy or dangerous.

They did drink beer a lot though but this didn’t mean they were drunk all the time.

For most of they day they drank a very light beer, with nearly no alcohol in it.

Sources;

Medievalist.net

Jim Chevallier

Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England

Life in Medieval Europe: Fact and Fiction

Witch burnings everywhere

For most of the Medieval era the church claimed witches didn’t exist and fought these superstitions.

When witches were caught, they were generally hanged.

Witch burning is from a later era.

Knight’s armour too heavy to move in

Averagely a full suit or armour weight no more than what modern day soldiers carry.

They have joints and are very flexible and the idea that if a knight fell he no longer could stand up or that they needed help being hoisted onto their horse is nonsense.

Bland and tasteless food

Just because many spices were not yet being imported from far away countries doesn’t mean people didn’t have access to other ways to give their food extra taste.

The medieval peasant had a well-rounded healthy diet that, depending on good harvests, kept them well fed, properly nourished as it wasn’t lacking anything major.

They ate meat stews, vegetables, bread, eggs, fish, fruit and dairy products.

And of course herbs from often their own garden such as parsley, rosemary, thyme, basil, garlic, chives and many others.

Enough to alter the taste of your meal dramatically.

Some would say that the Medieval diet in some way was healthier than the diet of processed foods many modern people have.

Of course those who were wealthy had access to more and different types of meat.

We know what peasants ate from archaeological research and we also have recipes that teach us what the rich ate and I can say from experience that they both are very tasty.

Sources;

New Scientist

Medievalists.net

University of Bristol

People never travelled

Although of course many people didn’t have chance or opportunity to travel, the idea of it being extremely rare for someone to never leaving their town or village is incorrect.

People went to fairs and markets in neighbouring towns but many also went on pilgrimage to visit shrines and relics, sometimes in quite distant places, travelling many miles.

Pilgrim’s badges and souvenirs have been found all over Europe and it was not just the rich and wealthy to made these journeys.

But also more common parts of life involved travel, for instance many children were taught a trade in another village of town and fairs and markets were traditionally a place where young people met each other and this often led to marriages, meaning that getting married in many cases also involved moving to another town.

And of course besides going to the market or fair for shopping or fun it was also a place where people had the opportunity to sell their own wares.

Trade was another reason for even the common people to travel to another village or town.

Think about this; if nobody travelled the Bubonic Plague would not have been able to reach so many corners of the world.

Not racially diverse

This relates to the previous point.

People travelled, a lot and especially in cities you would find merchants, sailors and pilgrims from all over the then known world.

Even smaller villages were visited by foreigners during markets, fairs, etc.

Of course Medieval society was not as racially diverse as it is today and I’m not saying that non-Europeans were common but the myth here is that Medieval Europe was not racially diverse AT ALL, with other words that Medieval Europeans would never see people with non-white skin anywhere.

But reality is that seeing for instance a black person in London wouldn’t have been a big deal, there had been black people in Britain since Roman times and there are several (mostly) late Medieval/early Elizabethan records that show groups of Persian, Indian and Moors living as free people in several areas in Britain, groups often big enough to be considered a small community.

There were many enough for Queen Elizabeth to in 1596 write letters to several cities telling mayors to deport these black people.

And Medieval Europe was not just England or Germany, it stretched all the way to Southern Spain and Italy where interaction with people from the African continent was even more common.

By the 1600s as much as 5–7% of the population in Portugal was black.

16th century London church records entries also show quite a few “moors” and “Negroes” who not just lived there but got married, had children, etc.

Recent DNA research on the remains found aboard the Mary Rose, the Tudor warship that sank in 1545, showed that two out of eight skeletons had North African heritage, making them very likely Arabs.

The salvage dive team of 1547 was led by Jacques Francis, a Guinean.

Archaeological examination of Plague burials in London also shows that 30% of people buried there were of (partial) African ancestry (source).

Of course racially diverse doesn’t have to mean black and white people, it also means Jews, Roma gypsies (since the 11th century), etc.

Even in literature/legend/folklore people with a non-white skin colour were present, three of the Knights of the Round Table were men of colour and “non Caucasians” were also heavily represented in Medieval European art.

Also in religion they were far from uncommon, Medieval Europeans knew of the Magi (the three wise men), the Egyptian Saint Maurice was a very popular black saint, etc.

This does not mean that people in small villages would have been used to seeing people from outside of Europe but it is not impossible either.

People travelled more than most people these days seem to think.

But yes, there were Medieval Europeans who would never see someone with another skin colour.

So; the Middle Ages lasted about a 1000 years and Medieval Europe was rather large.

I am not saying that ALL of Europe was racially diverse for ALL of the Medieval era, but saying ALL of Europe for ALL of the Medieval era was just white and people never ever saw dark skinned people or people of other races is a myth.

In this situation the word diverse is used to show that Medieval population of Europe was not as similar as people often think, not completely homogeneous.

Sources;

“Officially absent but actually present”: Bioarchaeological evidence for population diversity in London during the Black Death, AD 1348–50,’ by Rebecca Redfern and Joseph T. Hefner

Black Knights, Green Knights, Knights of Color All A-Round: Race and the Round Table

Black Central Europe

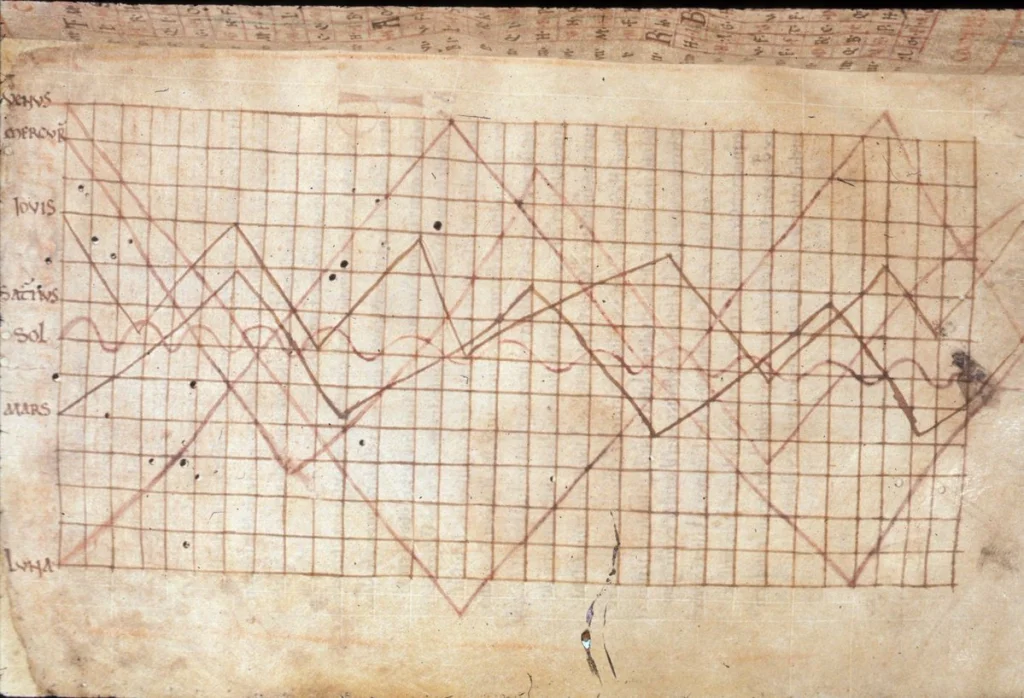

People were ignorant

Although education wasn’t available to all, the idea that the era was uneducated and ignorant is not correct.

It is often why the Medieval era (not just the early part) is still, incorrectly, called the ‘Dark Ages’ and defined as an era “characterized by ignorance, backward in learning, void of intellectual light”

The term is outdated and generally no longer used by what I like to call serious historians.

This idea of looking at the (early) Medieval era originated while the era was still going on, the person who developed the concept of ‘the Dark Ages’ is 14th century Francesco Petrarca/Petrarch.

Living in Rome and being a huge admirer of ancient Rome he, surprisingly, thought that everything had gotten worse after the collapse of the Roman empire.

His negative view of the previous centuries was political (he had power and quite a reputation) and biased.

In a way it is like any politician saying that when his people ruled the world everything was better.

Italian cardinal and ecclesiastical historian of the Roman Catholic Church Cesare Baronio coined the term “dark ages” as a way to describe the early Medieval era as a time of intellectual darkness but the term (and bad reputation was later used to describe all of the Medieval era, till quite recently.

It makes sense for Italians to think that things were great during the Roman empire and great when they got involved in the Renaissance and that everything between those two times was terrible.

The collapse after the Romans left of course did happen was nowhere near as big as people often seem to think, for starters life in Roman Europe somehow wasn’t fantastic for most people to begin with, it wasn’t as glorious an era as some think it was.

We all know the big cities and fancy villas but most people still lived as farmers or in little villages and they didn’t notice much of all those things the Romans ever did for them.

But there of course were some changes, from minimal ones that took centuries to take place in areas closer to Italy such as Gaul and Spain, to larger and more extreme ones at the outside of the empire, such as in Britain.

There was indeed a decline in technical capacity as the export and trade in certain goods such as ceramics and certain luxury goods came to a stop. Of course no longer being part of a colonial empire also meant a decline in long distance trade in general, it was not a good time economically speaking.

And there was also a decline in the knowledge of Greek as a language which did mean that an important source of knowledge became less accessible to the few that had access to it to begin with.

But Greek and Roman learning was never forgotten, the church had preserved it and those works that were no longer available were looked for and found by Christian scholars in the 11th century.

And the spread of Irish monastic schools (scriptoria) all over Europe laid the groundwork for the Carolingian Renaissance.

By the time the High Middle Ages Europe (1000-1250) was again taking the lead in scientific discovery.

Scholars also started translating old Greek but also Arabic texts, there was a lot of exchanging of ideas and knowledge going on, universities were established and scholars were encouraged to travel and have lectures all over Europe.

Of course Islamic and Jewish knowledge was of huge value but it was not necessarily non-European, people often forget that quite a large part of what we call Europe today was Islamic and Jewish, with other words, the distance between Medieval Europe and the Islamic or Hebrew world was not that big, in much of Europe Islamic and Hebrew knowledge, culture and science was part of life.

As often with science it is not one way traffic, when people interacted and cultures collided, clashed or combined, they learned from each other, then separately improved on it and then learned from each other again.

By 1200 translations of Ptolemy, Aristotle, Archimedes, Euclid and other Greeks and of Arab and Jewish writers Avicenna, Averroes and Maimonides had become available in Latin and expanded on and contributed to.

The Middle Ages ended when ‘The Renaissance’ started but the famous (overrated) Renaissance we all know (15th/16th century) was preceded by three other Renaissances!

The Carolingian Renaissance (8th and 9th centuries), Ottonian Renaissance (10th century) and the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Finally a short word on literacy.

We don’t really know how many people were illiterate in Medieval Europe.

As said before we’re talking about a rather long era and large area.

But at the time nobody really went door to door asking if people could read or write.

So we base our knowledge on what written sources are left and unfortunately much of what common people wrote has been lost.

We are left with books and documents written in Latin, mostly religious or about business.

How many people could read or write Latin?

Very few.

But how many people could read and write in their regional language, phonetically?

Probably quite a few, although again we’ll never really know.

Common people didn’t write on parchment or in expensive books with nice ink.

They wrote on wax tablets or bark, stuff that doesn’t last long.

I will expand on this later but want to leave you with one thing to keep in mind.

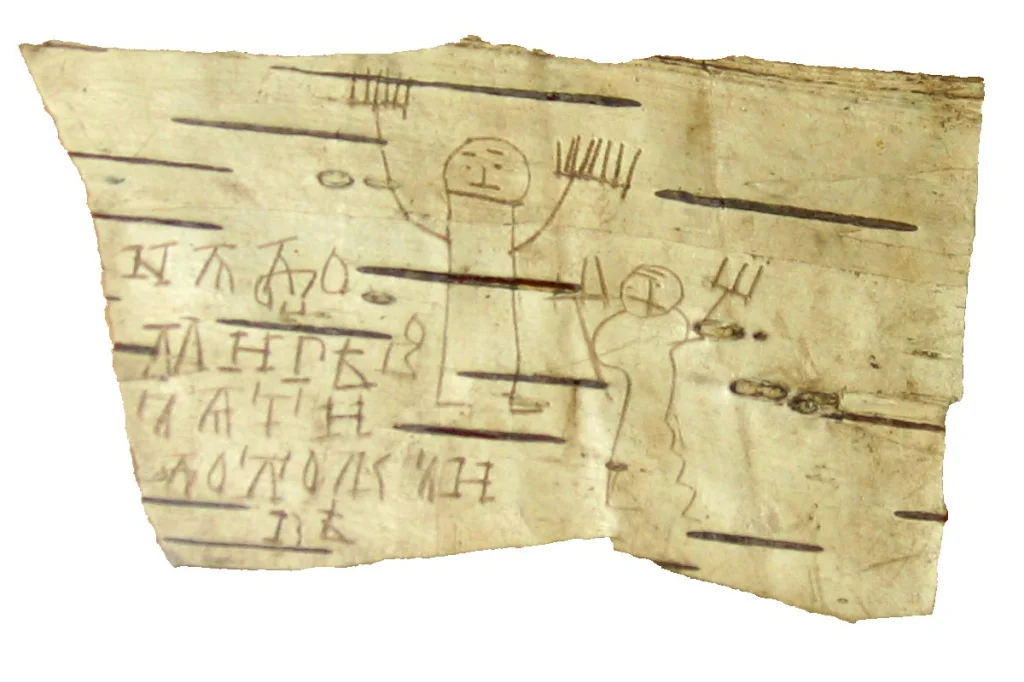

In the 1950s over 1000 birch bark writings were found in Russia, the unique condition of the soil in the region of Novgorod had preserved letters and drawings dating back to the 13th-15th century.

Over a hundred styluses were also found.

They were personal letters, business documents, very private messages, obscene stories and even school exercises and drawings made by children.

Most appear to have been written by common people and this find changed our ideas on literacy in that region at the time completely.

Also in the 1950s hundreds of medieval texts written on wood and bone were found in Bergen, Norway.

They are very similar to the Birch bark writings, they too appeared to have been written by common people.

We have proof of two places in and near Europe that shows us that common people were writing, we know that they used materials that are very rare to survive to the modern era.

So, I am not saying literacy was high, but I am willing to say that illiteracy wasn’t as high as we’ve long thought.

Conclusion; there were several periods characterised by significant cultural renewal in (Western) Europe during the Middle Ages and the idea of Europe totally collapsing after the Romans left was long exaggerated.

The Middle Ages was an era of (major) medical, cultural, scientific, philosophical, literary advancement.

(BL, MS Royal 13 A XI, f. 143v)

(BL, MS Royal 19 A IX f. 104, 106)

(BL, MS Harley 3017, f. 94)

Sources;

Erik Wade

Francesco Petrarca

Going Medieval

Medieval renaissances

Medieval philosophy

Medieval Medicine

Medieval science

On Medical Milestones, Being Racist, and Textbooks, Part I

On Medical Milestones, the Myth of Progress, and Textbooks, Part II

Slate

No medical knowledge

Although of of course the world of medicine wasn’t as sophisticated as today, the idea that doctors had no idea what they were doing and all Roman and classical knowledge having been lost is also incorrect.

There were clean and well managed hospitals and skeletons show examples of complicated medical procedures that were successful.

Progress in medicine didn’t come to a stop when the Roman Empire collapsed, of some Greek and Roman knowledge was lost but quite a few advancements in surgery, medical chemistry, dissection, and practical medicine were made in the Medieval era.

Theodoric of Lucca wrote in the 13th century;

” Every day we see new instruments and new methods [to extract arrows] being invented by clever and ingenious surgeons.”

Everyone of course knows de famous female physicians Hildegard of Bingen (if you don’t, shame on you), who wrote about how the hospitals worked, the training people got, etc.

Domestic pharmacy properly began during the Middle Ages and this of course had a huge effect on the future of medicine.

Did you know that Medieval cities had more hospital beds than most modern cities today?

In some cities they realised that sexually transmitted diseases were infectious and prostitutes were regularly checked for this reason.

And yes, they had anesthetics (made from mandrake root, opium, gall of boar and hemlock), they did external surgery on such things as facial ulcers and eye cataracts, they did internal surgery as well, to remove bladder stones for example and they learned how to use wine as an antiseptic.

Medieval surgeons removed arrows, dog bites, amputations, eye surgery and even brain surgery.

Another interesting quote;

“When you get up in the morning, stretch your limbs, so that the natural heat is stimulated. Then comb your hair because this removes dirt and comforts the brain. Wash your face with cold water to give your skin a good colour and to stimulate the natural heat.Clear your nose and your chest by coughing, and clean your teeth and gums with the bark of some scented tree.Exercise in moderation, because it is good to be tired; it stimulates the natural heat.”

Taddeo Alderotti, ‘On the Preservation of Health’, 13th century.

One could argue that our Medieval ancestors actually, in a way invented the hospital, pharmacies, eyeglasses, the concept of quarantine and more.

Sources;

British Library

Top 10 Medical Advances from the Middle Ages

Wikipedia

Theodoric of Lucca

Medievalist

Chirurgia by Roger Frugardi of Salerno (14th century)

Death penalty common

We know the medieval world to be one where you saw gallows everywhere and you could be hanged, burned, quartered and horribly tortured for the smallest crimes.

Although these things did happen, they were not as common as often suggested.

Executing someone or locking them up cost a community money and there were other ways to punish someone that were much better for those in charge.

In many cases people were ordered to pay a fine in stead or go on pilgrimage.

This made the community money or at least didn’t cost them anything and in stead got rid of the trouble maker for a while in a way that would perhaps help those who told the bad guy to go on pilgrimage get into heaven, give them access to the possessions left behind and with a bit of luck he never returned.

No table manners

The cliche of medieval people eating with their hands and throwing leftovers on the ground is also a myth.

For the upper classes and all those looking up to them, such as merchants and the new middle classes, eating properly with decent manners and etiquette was very important.

For peasants and commoners it would also make no sense because even leftovers had value and could often be used to feed animals, to make things with, etc.

Torches all over the place

We see this in all movies and tv shows, random torches everywhere, not just in castles but also in streets.

Like medieval street lighting.

They are there because when people make a film or tv drama they want to be sure you see what is happening.

In reality candles, torches, oil lamps all cost money.

Torches don’t burn very long, 30-40 minutes tops, they are sticks with some cloth and fuel (generally) and they work great for a little while but if you’d want them as actual lighting on a wall or street, you’d need someone, or several people to run around replacing them constantly.

Oil lamps and candles were a lot more common but also generally not cheap,

The rushlight (a dried pith of the rush plant soaked in fat or grease in a holder) was the most common light source besides the fireplace.

People used lights near them and when they went somewhere they carried them in a lantern.

Also the type of medieval torches used in castles that would burn longer than say 30-40 minutes didn’t look like we know from the films and tv dramas, in stead of a stick with some burnable material at the end they were long sticks entirely made of burnable material.

Sources;

Rushlights

Two finger salute

The insult where someone puts two fingers of one hand into the air with the back of the hand towards whoever they are saluting is not Medieval.

For a long time the story has gone around that this dates back to around the Battle of Agincourt where archers who risked losing their fingers if caught by the enemy, showed their fingers to show they still had them.

It is a great story but unfortunately there is no evidence whatsoever to support it.

The story that archers would get their fingers cut off is true, or at least it is true that they may have believed it as Henry V mentioned it in a speech before a battle once but he mentioned the removal of three fingers and this is the only mention we have of this and there is no evidence of it actually happening, it might just have been a bit of scare mongering propaganda.

Some medieval images do seem to show archers making the gesture but there’s no context to it, we don’t know why they do it or what it means.

But the most damning thing is that besides what I’ve just mentioned here there doesn’t seem to be any kind of evidence regarding the v-sign being used as an insult till the early 20th century.

It would be extremely unusual for an insult with such a strong origin story to completely die out for centuries and then out of nowhere return again.

In short; there is no real evidence that supports the V-sign insult relationship with Medieval archers.

Finally…

Several myths are busted in this wonderful funny and educational series; Terry Jones ‘Medieval lives’.

Make sure you check out all episodes;

Medieval Myths Bingo

from https://fakehistoryhunter.wordpress.com/2019/09/10/medieval-myths-bingo/